“All The Devils Are Here,” or the Reawakening of My Shakespeare Obsession

Thank you to Patrick Page and his Instagram.

Woo-hoo! Substack launched. Feeling excited — thank you for indulging me!

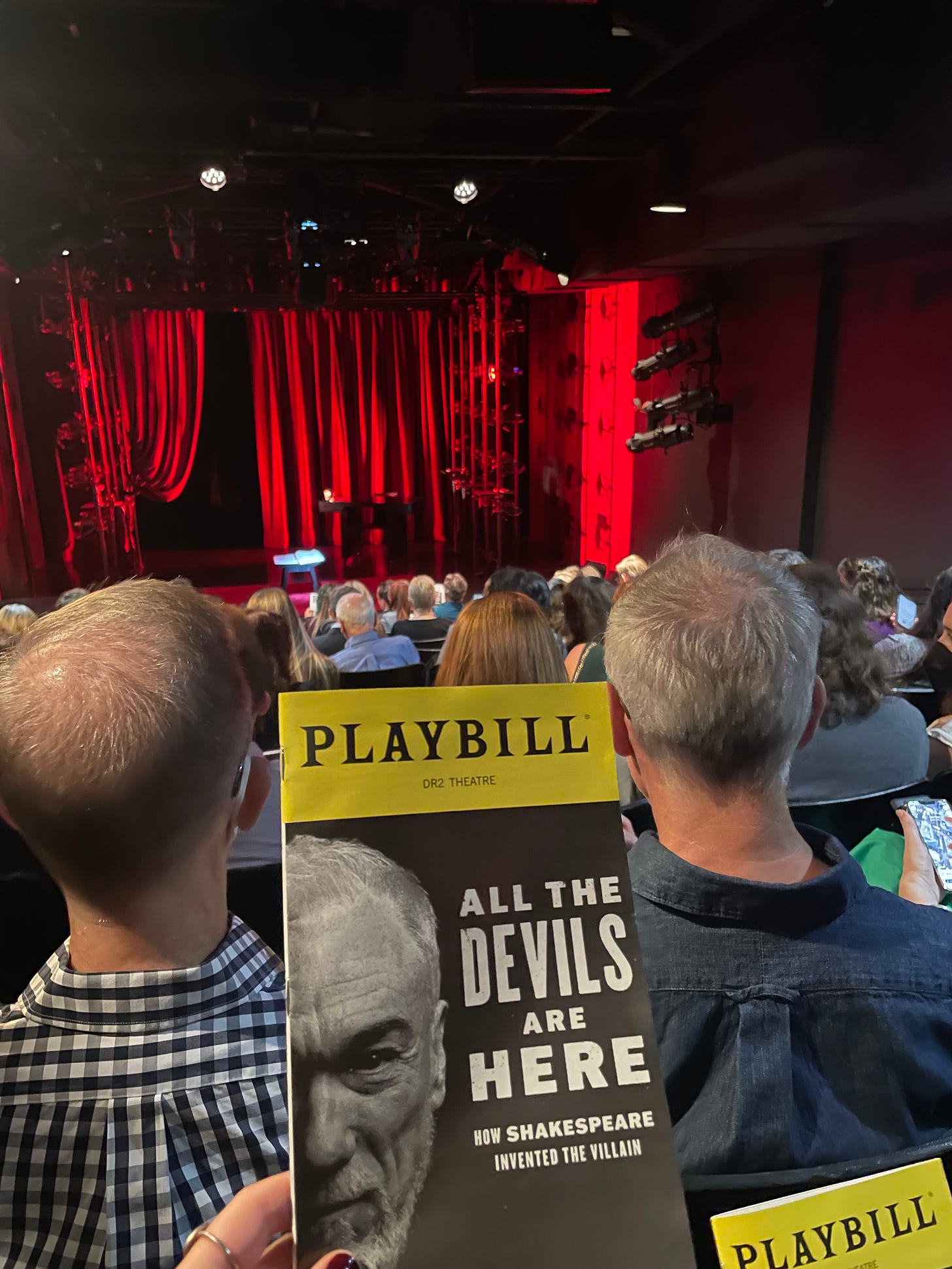

Today, we’re talking about one of my favorite plays of the year: “All The Devils Are Here,” a one-man show about Shakespeare’s villains.

Here’s the gist:

How I found out about it: Following Patrick Page on Instagram <3 His Instagram is peak older man on Instagram doing his thing and supporting his wife and I love it.

Why I went: Patrick Page and Shakespeare.

How I got tickets: Theatre Development Fund (TDF)! TDF offers discounted tickets to a variety of people — from people 30 and under and students to artistic professionals and union members. You’ll need to pay a membership fee (right now it’s $35 for the YEAR), then you’ll get access to dozens of shows at a lower cost. I paid $40 for this show when they’ve been going for closer to $100. I know this sounds like an ad, and that’s because it is. I just love that site.

In “All the Devils Are Here: How Shakespeare Invented the Villain,” Patrick Page plays many parts — from Iago in “Othello” to Malvolio in “Twelfth Night” — but perhaps his best one is teacher.

This 90-minute play is less of a show than it is a masterclass in acting and Shakespeare. Patrick Page (Green Goblin in “Spider-man: Turn Off the Dark,” Hades in “Hadestown”) gives context for each of the villains he plays, not only on their specific situation, but also where Shakespeare was in his life and the world when he wrote them.

The show starts with an eerie scene from “Macbeth,” with Page embodying Lady Macbeth, his famously bass voice echoing around the small theater. In a flash, the lights go up, and Page is standing before us, laughing, smiling, asking if we were frightened. He’s quickly shaken off the darkness of the villain he just fully inhabited. Now, he approaches the audience as if we’re in a conversation, as if he’s teaching a college class.

It’s this teaching that unlocks so much for the audience. Shakespeare without context can be beautiful, but also confusing and even frustrating. The reason I love Shakespeare is because I’ve had the privilege of incredible teachers. Peter Royston, the director of the Shakespeare camp I attended for multiple summers, broke down the language, plot, and characters for my fellow campers and I so we felt excited about acting Shakespeare. We understood what our characters were saying and what they wanted and why they were saying it. Education, especially with something less accessible like Shakespeare, is empowering. It feels like you’ve been given a key to something almost secret, something special.

Page teaches the audience by giving us the context that is needed to fully enjoy, react to, and understand the characters, and in doing so demonstrates just how masterful and passionate an actor he is. Even if the show was just a series of changes between characters, my review of his acting would be the same: transformative. Yet with the guidance, it’s almost as if you can see the acting choices Page is making in his head.

Page discusses religion and antisemitism in Shakespeare’s time and his personal life, then sets us up with a version of Shylock from “The Merchant of Venice” with new understanding: someone who has been persecuted, someone who is bitter, someone who is looking for revenge. He tells us about Shakespeare’s darker and more mentally complex villains, and what it was like to research whether Iago from “Othello” is a psychopath — and goes down the list of psychopathic tendencies for us all to hear, then acts them out. We learn about perspectives on disability in the Elizabethan Era (spoiler alert: not good!), then watch Page inhabit Richard III in that context.

When the play is over, the closeness between audience and actor doesn’t end. Rather, Page hosts talkbacks after every performance, encouraging the audience to ask him questions not just about the show, but also about his process, Shakespeare, and the world. My audience threw him a couple of doozies, including one about how he “handles evil knowing the state of the world.” Page handled these questions with grace, offering the same thoughtfulness and care he does this material, these characters, even when we know them as villains.

In a way, “All the Devils Are Here” is an extension of empathy. Page helps us try to understand who these villains are, to give us the right context before we hear them.

It’s one thing to go to the theater and watch someone do something wonderful; it’s another to be guided along as they do that wonderful thing. “All the Devils Are Here” is an invitation. It’s one I recommend everyone take, even if Shakespeare isn’t your typical go-to theater.